January 27, 2022

If you switch on the television, surf the internet or check out Instagram, you'll quickly learn every detail about the life of your favorite actor or singer. It makes sense in some ways — the top celebrities offer groundbreaking performances, and their work may touch the lives of many people. But when it comes to the life of medical researchers — who perform groundbreaking work that is literally lifesaving — we know very little. We are quick to enjoy the benefits of the new and innovative treatments but have no idea what it takes to actually develop them.

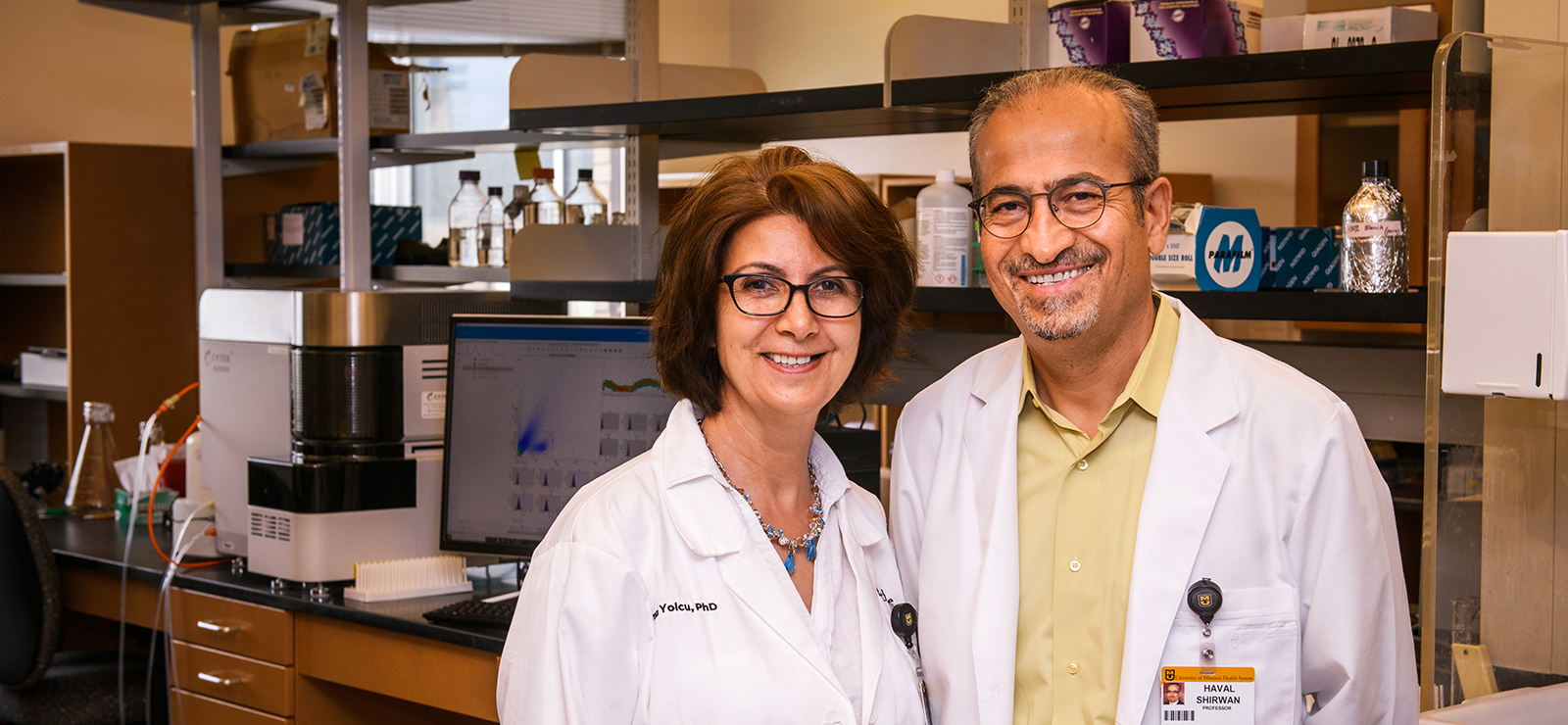

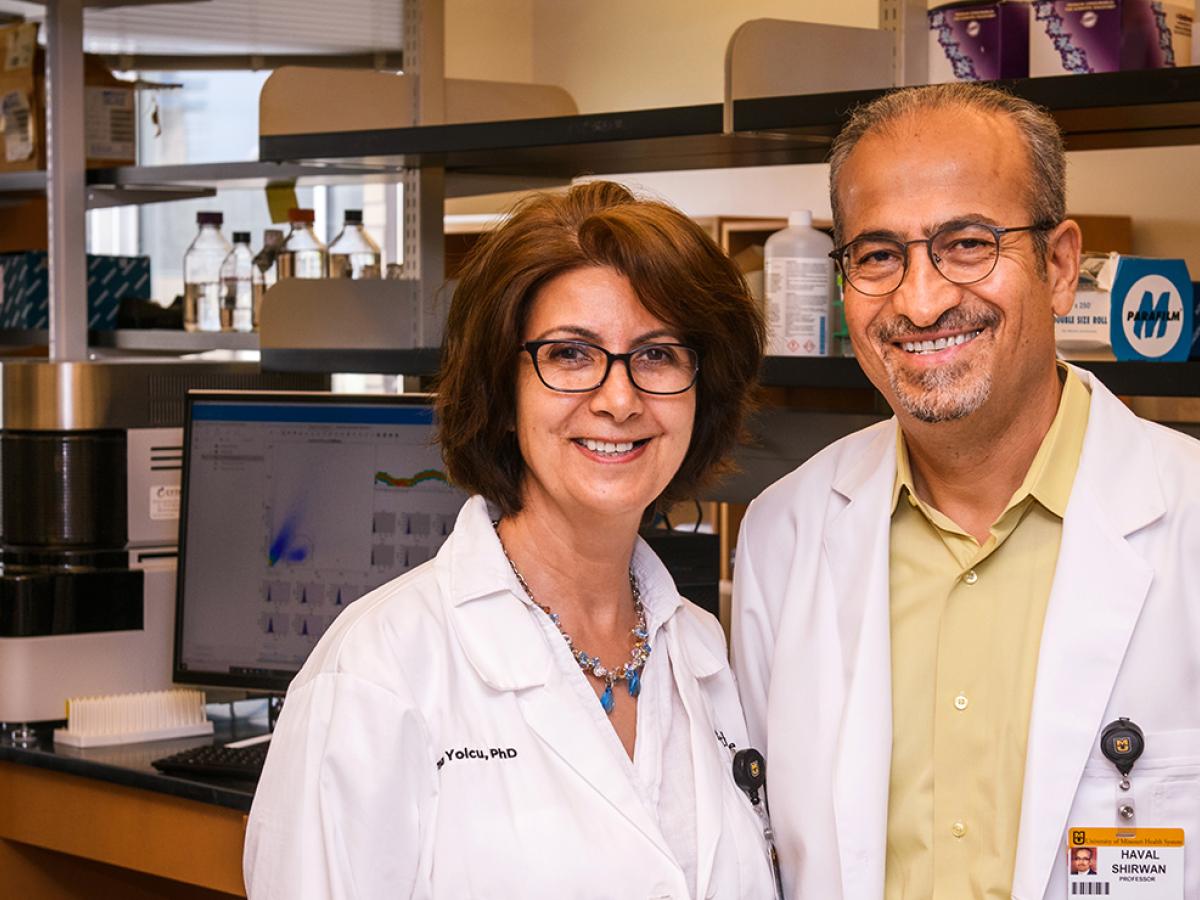

To understand what life is like as a medical researcher, we spoke with married couple Haval Shirwan, PhD and Esma Yolcu, PhD. They both work as researchers and professors with the University of Missouri School of Medicine. While they don't always work together on the same projects, Dr. Shirwan and Dr. Yolcu are currently engaged in a joint research effort — and a pretty impressive one at that. Several organizations, including the U.S. Department of Defense and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), have awarded them grants to study and test a new (and potentially life-changing) treatment for people with Type 1 diabetes.

"When you go to a hospital for a treatment, you take a pill or you get an injection, there is tremendous effort and hard work behind that product," Dr. Shirwan says. "It takes a lot of time and resources." It also takes a lifestyle that works around a researcher's dedication to science.

Outside of the lab, Dr. Shirwan and Dr. Yolcu have two children, the younger still in high school and the older attending college. After decades living as researchers, parents and spouses, they admit their career choice directly impacts how they live — and they wouldn't change a thing about it.

Dr. Shirwan and Dr. Yolcu shared five truths about life as a medical researcher:

1. Discoveries Don't Come Easy — A Researcher's Career Is Mostly Spent Looking for Answers

When you think of medical research, it's easy to envision major breakthroughs and the legacy that comes with them. But most of the time, researchers focus their energy on ideas or concepts that don't end up working. On the upside, those failures move the scientific process forward, and when a concept has real potential, it's invigorating.

Dr. Shirwan uses an analogy to explain how scientific discovery feels: "Imagine you are in a room with no windows or light," he says. "And you stay in that darkness for months and months and suddenly, you see a spark. That spark basically keeps you going to endure those conditions. Once you see something positive or get a positive result, you forget about everything else, and that kind of carries you through life."

The multiple grants awarded to Dr. Yolcu and Dr. Shirwan are the result of a spark they saw more than 25 years ago. Now, after more than two decades of research and effort, their concept is transforming from an idea to a potential medical breakthrough.

2. A Researcher's Mind Is Constantly Engaged in Science, Even Outside of the Lab

Researchers, like anyone else, need to give attention to the day-to-day details of life and raising a family. But science is never far from their minds.

"For me, science rules my world," Dr. Shirwan says. "It is something that always engages my mind and gives me a tremendous boost of energy, no matter what the circumstances."

Dr. Yolcu and Dr. Shirwan begin their workday, every day, with a walk together. They limit that walk as much as possible to scientific discussion. Talk of the kids' schedules, what's for dinner or whose turn it is to take out the trash is typically saved for another time and place.

But that walk certainly isn't the only time they talk shop — in fact, the kids sometimes need to remind them that it's "too much science talk" at the dinner table. They admit that they wake up thinking about it and take it to bed at night, especially when they are working on a new concept.

3. Researchers Have to Work Hard to Find Work-Life Balance

As for a lot of people, finding balance between work and home is tough. Researchers, who work at the lab 10 to 12 hours a day, are no different.

Dr. Yolcu, like most working moms, found it especially challenging to balance work and home when the children were young. Being a wife and a mother added so many other responsibilities to the challenges she already faced as a female scientist.

"Young children need their mom all the time. And I'd go and take them for after-school activities, but at the same time, deep inside I felt pressure that I needed to catch up at work, because I was competing with colleagues who could be extremely focused on their research," she says. "But I hung in there, because I knew without science, I would be a very unhappy person. And I'm glad I did because it got easier after the first five years."

Today, Dr. Yolcu maintains her balance by spending time outside each morning and practicing daily meditation with a focus on gratitude. Dr. Shirwan says his formula for balance is waking with a positive attitude and never missing his daily walk. They both like to read and carve out time for material that's not related to their work. They are also diligent about taking time off as a family twice a year to travel. It's not always easy to be away from their work, but they know it's valuable.

4. The Best Research Is Not Done Alone

Many might imagine the work of a research scientist is lonely. But that couldn't be further from the truth. A critical element to scientific success is collaboration. Medical researchers like Dr. Shirwan and Dr. Yolcu conduct investigations that are highly complex, and it's a collective effort.

"It takes a lot of work on the part of a lot of people with different expertise to bring an idea from conception to the clinic to the bedside," Dr. Shirwan says. "We have limitations as scientists, and it's almost impossible to solve everything on our own. Seeking input is good in the scientific field — it's how science progresses."

For Dr. Shirwan and Dr. Yolcu, the colleague they rely on most also happens to be a spouse. "We look at each other's work from a scientific perspective," Dr. Yolcu says. "His input often helps me reshape my aims and my proposals, and he comes and discusses his cases with me."

5. The Environment Where a Researcher Works Matters

Medical researchers mostly conduct their work in university, hospital or government laboratories and require a variety of equipment. Dr. Yolcu believes that working in an academic health system is vital to their work.

"As a scientist, having a health care system on the same campus and under the same umbrella helps in a big way," she says. "We can see and hear from our commission colleagues about what the needs are in the clinic and what the issues are. That is what helps us shape our research and our scientific direction."

They recently began conducting their research in the new NextGen Precision Health building, and Dr. Shirwan is excited about the new possibilities. "My excitement is about a building not only with cutting edge facilities and equipment," he says, "but also allowing investigators with different sets of expertise and research interests to work under the same roof. This initiative is extremely visionary and timely."

Next Steps and Useful Resources

- Want to learn more about research at MU Health Care? Check out our NextGen Precision Health initiatives.